The Matawan Man-Eater: The Real-Life Jersey “Jaws”

Nearly 60 years before Peter Benchley’s novel “Jaws,” a real man-eater lurked the waters of the New Jersey coast. A single shark was responsible attacks on five victims, killing four. One has to wonder–could it happen again?

Nearly 60 years before Peter Benchley’s novel “Jaws,” a real man-eater lurked the waters of the New Jersey coast. It was July 1, 1916, and in Beach Haven the tourist season was in full swing. The beaches were filled with sunbathers and the ocean with swimmers. Everything seemed like just another hot July day. But this day would be different from any other.

Nearly 60 years before Peter Benchley’s novel “Jaws,” a real man-eater lurked the waters of the New Jersey coast. It was July 1, 1916, and in Beach Haven the tourist season was in full swing. The beaches were filled with sunbathers and the ocean with swimmers. Everything seemed like just another hot July day. But this day would be different from any other.

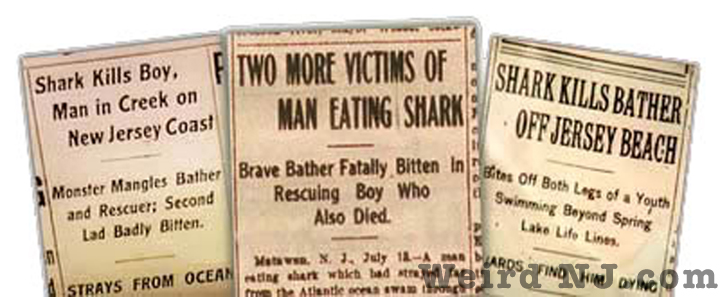

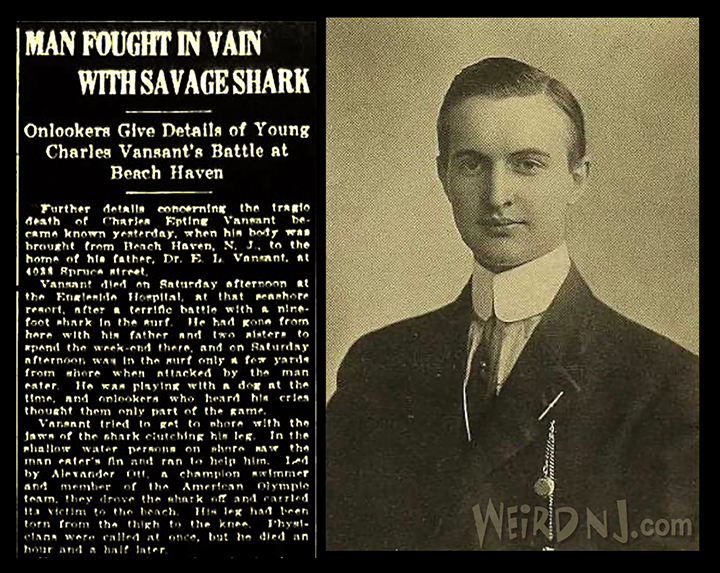

Charles Epting Vansant, 28, of Philadelphia, was on vacation at the Engleside Hotel with his family. Before dinner, Vansant decided to take a quick swim in the Atlantic with a Chesapeake Bay Retriever that was playing on the beach. Shortly after entering the water, Vansant began shouting. Bathers believed he was calling to the dog, but a shark was actually biting Vansant’s legs. He was rescued by lifeguard Alexander Ott and bystander Sheridan Taylor, who claimed the shark followed him to shore as they pulled the bleeding Vansant from the water. Vansant’s left thigh was stripped of its flesh; he bled to death on the manager’s desk of the Engleside Hotel at 6:45 PM.

Most people along the Jersey Shore wrote the attack off as a singular freak occurrence. They could not have been more wrong.

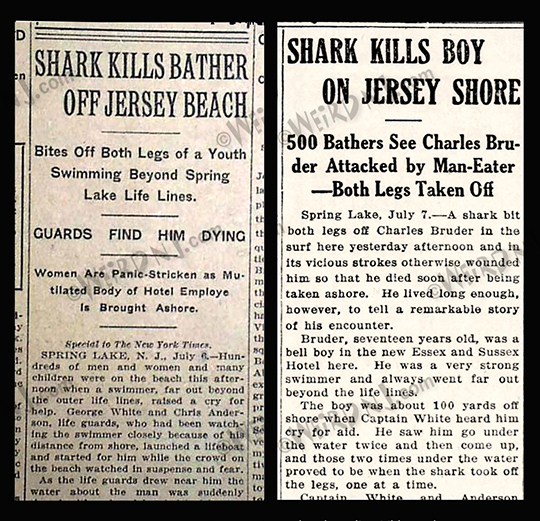

Five days later the shark would strike again, 45 miles to the north in Spring Lake. The victim was Charles Bruder, 27, a Swiss bell captain at the Essex & Sussex Hotel. Bruder was swimming 130 yards from shore when he began screaming “A shark bit me! Bit my legs off!” These are the last words Charles would ever utter.

A shark bit him in the abdomen and severed his legs. Bruder’s blood turned the water red. Lifeguards Chris Anderson and George White rowed to him in a lifeboat and realized he had been bitten by a shark. They pulled him from the water, but he bled to death on the way to shore.

The Matawan Man-Eater

Mesh barriers went up almost immediately around swimming areas along the coast. What would happen next would elevate the panic to a new level. Thirty miles farther north, residents of Matawan, a small town 11 miles inland from the open ocean, naturally felt that they were safe from attacks. Swimmers here were confined to the Matawan Creek, a narrow tidal creek that wound its way to the bay. A retired fishing boat captain, Thomas Cattrell, was walking home after a successful day of fishing. When he crossed over Matawan’s new trolley drawbridge he noticed something that seemed almost impossible: a huge shark was heading up the inland waterway. He couldn’t believe his eyes, but confident that what he saw was very real, Cattrell ran into Matawan to warn everyone.

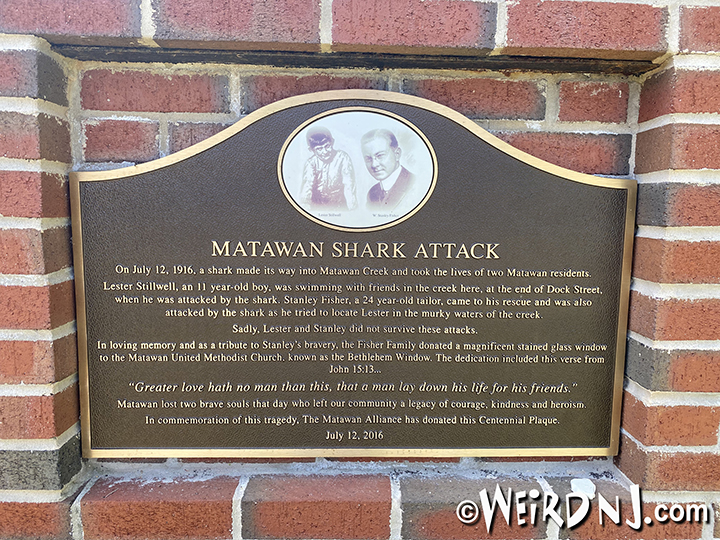

Though the citizens were all aware of the two shark attacks on the coast, no one could really believe there was any great threat of an attack in a small body of fresh water. Despite his vigorous pleas, the Captain’s story was dismissed as a heat induced phantom. Ignoring these warnings would prove a very grave mistake. On July 12th a factory across town was generously letting 11-year-old Lester Stillwell leave work a little early. After meeting some friends, they went for a swim in the Matawan Creek. While they splashed and played, Lester told his two friends, both only a few feet away, to watch him floating on his back. A moment later he was violently pulled beneath the water’s surface. His friends listened in disbelief to his screams as he bobbed up and down. Blood filled the water around him as the shark dragged him under again and again. His friends swam as fast as they could and then ran into town screaming and crying. The boys’ impassioned cries for help would not be ignored. 24-year-old Stanley Fischer sped to the creek with two other men thinking that Lester may have suffered an epileptic seizure. The two men dove in, not knowing there was a shark still attacking the boy’s corpse. Stanley Fischer attempted to pull the bloody body away from the shark and was also attacked. He died a few hours later at Monmouth Hospital in Long Branch. But the NJ man-eater was not yet finished.

Heading back down the brackish tidal stream towards the ocean the shark struck again within one hour of the last attack, wounding 12-year-old Joseph Dunn who only narrowly escaped with his life, but not without losing a leg. He would be the 5th and final victim of the marauding fish.

After a two day search of the creek young Lester Stillwell’s body was found on July 14th, 150 yards upstream.

Now the town of Matawan, stunned by the gruesome and unlikely attacks, was out for revenge. A reward was offered for the shark, and the people of Matawan became obsessed with vengeance against this evil creature. Some of the townspeople industriously filled the creek with dynamite, hoping to blast the shark into oblivion. The dramatic effort proved unsuccessful. Back on the coast the greatest shark hunt in the state’s history was under way. Although no one knew the species, or its size, blind retribution would be swift. Hundreds of sharks were caught and slaughtered. Shortly after the attack Michael Schleisser, a coastal fisherman, captured the man-eater just outside a creek at the Raritan Bay. It was an eight and a half foot Great White,* and when dissected, 15 pounds of various human remains were allegedly discovered in its stomach. For many, the grisly discovery brought closure to the summer’s horrific events.

the shark, and the people of Matawan became obsessed with vengeance against this evil creature. Some of the townspeople industriously filled the creek with dynamite, hoping to blast the shark into oblivion. The dramatic effort proved unsuccessful. Back on the coast the greatest shark hunt in the state’s history was under way. Although no one knew the species, or its size, blind retribution would be swift. Hundreds of sharks were caught and slaughtered. Shortly after the attack Michael Schleisser, a coastal fisherman, captured the man-eater just outside a creek at the Raritan Bay. It was an eight and a half foot Great White,* and when dissected, 15 pounds of various human remains were allegedly discovered in its stomach. For many, the grisly discovery brought closure to the summer’s horrific events.

It was now apparent that a single shark could be responsible for all of these attacks. In the summer of 1916 no one had yet imagined that so many could fall victim to a lone and vicious killer.

It was now apparent that a single shark could be responsible for all of these attacks. In the summer of 1916 no one had yet imagined that so many could fall victim to a lone and vicious killer.

* Though the killer shark was initially reported to be a Great White, many experts now dispute the original reports and believe the killer was more likely a Bull Shark.

Matawan Man-Eater Trestle Tribute

If the image of the toothy shark jaws below look familiar to you it’s probably because at some point you, like just about everyone else, has been terrified by either the book or movie “Jaws”. And the story that inspired this mural is actually the exact same incident that inspired New Jersey author Peter Benchley to write that harrowing novel in 1974.

This arched railroad trestle found along the New Jersey Southern Railroad line (Central Railroad of New Jersey) spans the narrow muddy waters of the Matawan Creek, just yards away from the location where in 1916 two young men lost their lives, and another lost his leg to a marauding killer shark. (You can read all about the artist who painted the mural in his exclusive interview with Weird NJ.)

Looking at Matawan Creek today it seems almost inconceivable that a shark capable of such carnage could find his way into this tepid body of water. Yet seeing his mural, easily visible from Matawan’s Aberdeen Road, one can hardly help but wonder – if it happened once, couldn’t it happen again?

View this post on Instagram

The preceding article is an excerpt from Weird NJ magazine, “Your Travel Guide to New Jersey’s Local Legends and Best Kept Secrets,” which is available on newsstands throughout the state and on the web at www.WeirdNJ.com. All contents ©Weird NJ and may not be reproduced by any means without permission.

Visit our SHOP for all of your Weird NJ needs: Magazines, Books, Posters, Shirts, Patches, Stickers, Magnets, Air Fresheners. Show the world your Jersey pride some of our Jersey-centric goodies!

Now you can have all of your favorite Weird NJ icons on all kinds of cool new Weird Wear, Men’s Wear, Women’s Wear, Kids, Tee Shirts, Sweatshirts, Long Sleeve Tees, Hoodies, Tanks Tops, Tie Dyes, Hats, Mugs & Backpacks! All are available in all sizes and a variety of colors. Visit WEIRD NJ MERCH CENTRAL. Represent New Jersey!

![]()